LB/Festival de Vídeo Online

A cada semana, a partir do dia 28 de abril, a Luciana Brito Galeria disponibilizou um novo vídeo, uma nova experiência, que ficará em nosso site por tempo indeterminado. Assim, você pode ver e rever, quantas vezes e quando quiser. O objetivo foi propor uma reflexão sobre um conjunto significativo de trabalhos tanto de artistas que são representados por nós, quanto de outros que achamos relevantes para a proposta. O vídeo da semana é "Photokinetic" (2020), de Héctor Zamora (México). Acompanhe!

Curadoria: Analivia Cordeiro

Texto Curatorial: leia aqui

Alvos, 2017

Video

Cor, estéreo

Duração: 06’20''

Produção e edição: Marcia Beatriz Granero

Assistente de produção: Luiza Calmon

Finalização: Yuri Amaral

Fotografia: Fabio Bardella

Desenho e mixagem de som: Gustavo Vasconcelos

Edição: 2/5 + 1 P.A.

© cortesia Galeria Millan

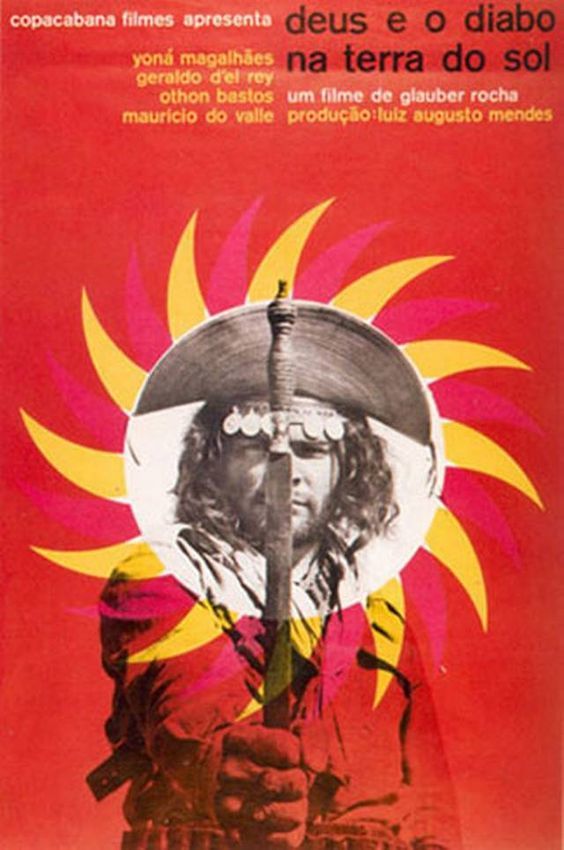

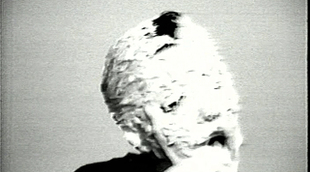

Durante o processo de pesquisa para a produção de “Alvos” (2017) Lenora de Barros se deparou com alguns exemplares de alvos usados nos clubes de tiro. Ficou impactada com a carga de violência contida nessas figuras em ‘decomposição’ após os tiros que receberam – imagens de corpos que nunca viveram, mas morreram de forma violenta. Os alvos utilizados em academias de tiro são um elemento incômodo e perturbador num tempo em que a violência se dissemina de maneira assustadora e se volta contra alvos determinados, mas também aleatórios.

O vídeo foi gravado numa dessas salas de academia de tiros em São Paulo, em Setembro de 2017, e no qual, durante a ação, a artista posicionou a figura do alvo como máscara em seu próprio rosto. O que chamou sua atenção na imagem desse alvo, é o fato de o ponto que direciona o tiro estar situado em cima da boca. Essa conexão simbólica com a língua e a linguagem interessa a arista. A Linguagem e a Comunicação sob ataque e risco de interdição, crise da comunicação, e a violência simbólica.

Lenora de Barros

1953, São Paulo, SP. Vive e trabalha em São Paulo, SP.

Formou-se em linguística pela Universidade de São Paulo. Lenora de Barros é uma grande expoente da poesia visual, linguagem cuja origem remonta ao movimento da poesia concreta dos anos 1950, período também marcado pela gênese de uma forte abordagem construtivista e vanguardista na arte brasileira. A prática da artista se iniciou nos anos 1970, como desdobramento dessas fortes correntes das décadas anteriores, onde a palavra e a imagem apresentavam-se como seus materiais primordiais. Desde então, seu foco volta-se para a exploração das possibilidades dos códigos dessas linguagens que ela articula através de diversos suportes, tais como vídeo, performance, fotografia, instalação sonora e a construção de objetos.

-

Héctor Zamora, Photokinetic, 2020

-

Re-Construtivo, 2020

Analivia Cordeiro

-

Forest Warrior – Xondaro Ka’aguy Reguá, 2020

ANGRY duo (Bruno Silvia e Gabe Maruyama)

-

Ouragualamalma, 2020

Eder Santos

-

Encruzidança, 2018

Kelly Santos e Naná Prudêncio

-

Vidbits, 1974

Alvy Ray Smith

-

Do Peito ao Prumo, 2020

Tothi dos Santos

-

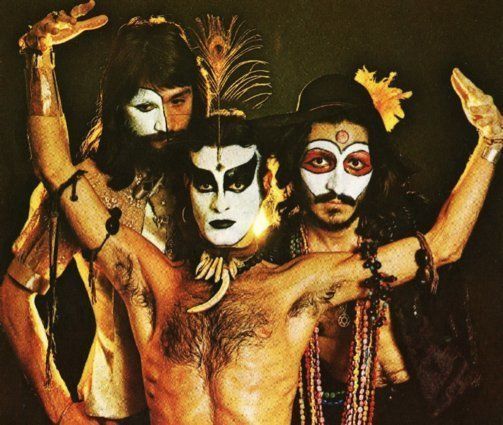

The Trip, 1976

José Roberto Aguilar

-

Sunstone, 1979

Alvy Ray Smith

-

Tudo Está Dito, 1974

Augusto de Campos

-

Hommage a Mondrian, 1972

Jean Otth

-

Flesh I e Flesh II, 2004

Analivia Cordeiro

-

Limiar, 2015

Regina Silveira

-

Homenagem a George Segal , 1985

Lenora de Barros

-

Bronze Revirado, 2011

Pablo Lobato

-

Landscape for White Squares, 1972

Anthony McCall

-

VT Preparado AC/JC, 1985

Walter Silveira e Pedro Vieira

-

Places of Power, Waterfall, 2013

Marina Abramovic

-

Una Milla de Cruces Sobre el Pavimento, 1979

Lotty Rosenfeld

-

Alvos, 2017

Lenora de Barros

-

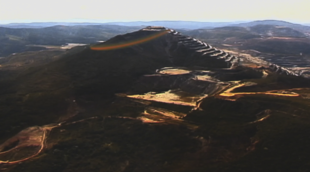

Ituporanga, 2010

Caio Reiseiwtz

-

Nas Coxas, 2018

Héctor Zamora

-

Non Plus Ultra, 1985

Tadeu Jungle

-

Há Casas, 2018

Rochelle Costi

-

0=45 Versão I, 1974

Analivia Cordeiro

-

Dormindo Acordada, 2011

Fabiana de Barros & Michel Favre

-

Earthwork, 1972

Anthony McCall

-

O Pulsar, 1975

Augusto de Campos

-

Actualidades / Breaking News, 2016

Liliana Porter

-

Campo, 1976

Regina Silveira

-

Tumitinhas, 1998

Eder Santos

-

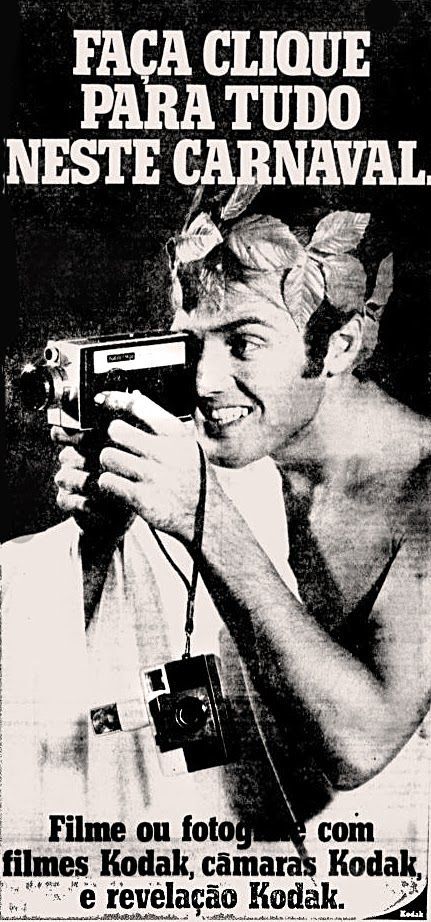

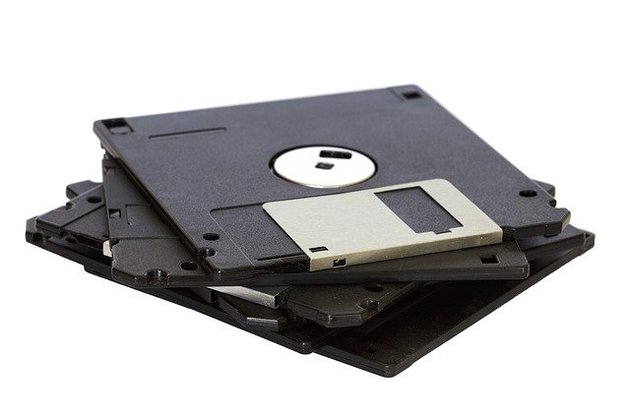

Corda, 2014

Pablo Lobato

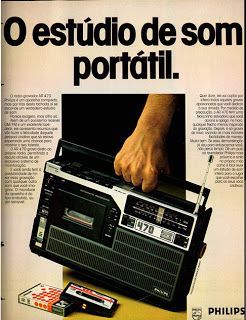

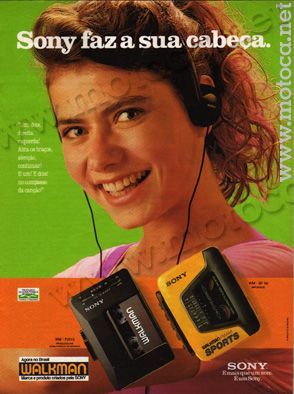

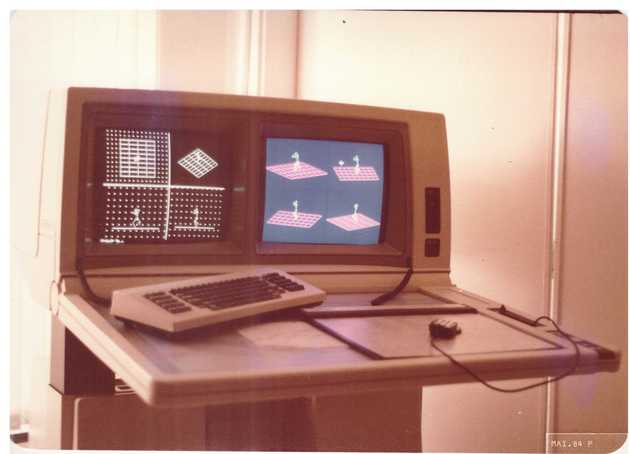

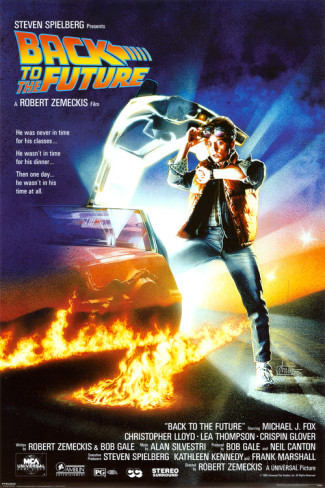

Aqui você verá vídeos históricos. Enquanto uns são praticamente inéditos, outros são consagrados pela história da arte. Em seus mais de 50 anos de existência, a vídeoarte é uma mídia que se caracteriza por sua enorme flexibilidade. Os formatos destes vídeos passaram por mais de dez variações: desde o início, com as grossas fitas U-Matic ou Betacam, por exemplo, até os pequenos e atuais pen-drives com suas enormes capacidades. Conhecer as transformações as quais essas obras sofreram é, hoje em dia, muito mais interessante do que se poderia pensar, considerando a acessibilidade atual da tecnologia, além da possibilidade de conhecer as fontes originais nos faz compreender que são justamente esses instrumentos que formatam o nosso mundo e a nossa percepção. Esta exposição tem o objetivo de mostrar como esses dispositivos existentes no passado podem nos ajudar a compreender e complementar o resultado artístico como um todo.

O modo de exibição também variou muito: hoje existem inúmeras plataformas, desde celulares de pequena dimensão, até projetores 4K – Ultra HD, com grande extensão e qualidade excepcional. Mais uma vez, seguindo os rumos e as necessidades da nossa história, essa arte se reinventa e adquire um valor único quando entendemos, sentimos, compartilhamos e discutimos sua capacidade em traduzir um momento histórico, um lugar geográfico específico, ou mesmo um comportamento particular que se torna universal.

Neste momento de isolamento social, a câmera de vídeo ganhou status de principal meio de comunicação visual, o único canal entre aqueles a quem queremos comunicar. Com isso em mente, podemos avaliar o significado de se expressar através de uma câmera. Podemos ainda compreender melhor a razão da qual os artistas escolheram este recurso para contar suas histórias e se posicionar no mundo, ressignificando-o através das lentes e do olhar do espectador.

Mesmo hoje sendo tão próxima de nós, a câmera de vídeo nos impõe condições e a principal delas é que tudo o que queremos expressar deve se encaixar dentro de um retângulo, presente em todos os dispositivos de exibição de vídeo, desde aparelhos celulares até datashows. Ao mesmo tempo, há o desafio de fazer com que o espectador perceba a mensagem e seja instigado a imaginar o que acontece fora deste retângulo. É um jogo, e ao mesmo tempo, uma ditadura: a ditadura do retângulo. Nessa obrigação de enquadrar o mundo dentro de um espaço restrito condicionamos nosso cérebro a pensar assim e nossa percepção se altera de acordo com esses padrões. Vemos a realidade como algo a ser adaptado pelo nosso principal instrumento atual de expressão: o vídeo.

O vídeo é visual e sonoro, mas é a realidade que nos oferece as sensações físicas. O grande desafio para o artista, dessa forma, é transmitir a riqueza e a complexidade da realidade com os recursos limitados dessa tecnologia. É intrigante observar como a genialidade e talento de cada artista provoca em nós sensações que vão além das restritivas soluções técnicas e até das experiências humanas. Através desse retângulo e dos recursos audiovisuais, cada artista cria sua poética e compõe uma obra única. Além disso, independente da percepção individual do espectador, há de se considerar o significado histórico e artístico contido em cada vídeo. É importante ainda apreciar os aspectos diversos do contexto de cada período, seus valores e possibilidades. Por isso, cada uma dessas obras pode ser vista mais de uma vez, e a cada oportunidade surge um novo olhar, assim como acontece com as telas penduradas nas paredes. Assim como a pintura, o vídeo também é uma tela, mas com movimento e som: este é o princípio base da vídeoarte.

Nenhuma outra mídia conseguiu trilhar tão bem o caminho para a contemporaneidade como a vídeoarte. Ao longo de sua trajetória foi eliminando os obstáculos, aperfeiçoando-se, até conquistar seu lugar definitivo nas artes visuais. Não só foi assimilada como recurso pelas mais diversas linguagens, como carrega em si a capacidade de agregar os elementos da arte, como por exemplo a tradição clássica da tela emoldurada ou a narrativa literária. Nesse sentido metalinguístico, como ela pode ser renovadora? Pense nisso enquanto assiste aos vídeos.

Os vídeos aqui escolhidos para serem apresentados online são legítimos, de alta qualidade artística, concebidos primeiramente para serem mostrados em formato original. Trata-se de uma curadoria genuína e autêntica, realizada para transmitir as ideias e as formas de pensamentos que nos fazem pensar, além de nos envolver com as poéticas intrigantes das épocas em que foram concebidos.

Ao assistir aos vídeos, permita-se transportar para o período em questão: anos de 1970, 80, 90 ou os anos 2000, e ao mesmo tempo experiencie com eles o que há de universal e duradouro.

Analivia Cordeiro,

março 2020

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Analivia Cordeiro, PhD, bailarina, coreógrafa, videoartista, arquiteta, pesquisadora corporal, curadora da coleção Waldemar Cordeiro. Considerada a primeira videoartista do Brasil (1973) e uma das pioneiras da computer dance mundial, criou vídeos, espetáculos multimídia, o software Nota-Anna de notação de movimento humano e um sistema de alfabetização de português em vídeo. www.analivia.com.br

Em breve você verá aqui a programação completa da exposição.