LB/Festival de Vídeo Online

A cada semana, a partir do dia 28 de abril, a Luciana Brito Galeria disponibilizou um novo vídeo, uma nova experiência, que ficará em nosso site por tempo indeterminado. Assim, você pode ver e rever, quantas vezes e quando quiser. O objetivo foi propor uma reflexão sobre um conjunto significativo de trabalhos tanto de artistas que são representados por nós, quanto de outros que achamos relevantes para a proposta. O vídeo da semana é "Photokinetic" (2020), de Héctor Zamora (México). Acompanhe!

Curadoria: Analivia Cordeiro

Texto Curatorial: leia aqui

Una Milla de Cruces Sobre el Pavimento, 1979

Vídeo

Duração: 04’29”

Edição: 16/25

Chile

© Gallery 1 Mira Madrid

Una Milla de Cruces sobre el Pavimento, 1979. (Uma milha de cruzes sobre o asfalto, 1979)

Intervención en espacio público, 1980. (Intervenção em espaço público, 1980)

A obra de Lotty Rosenfeld (Santiago de Chile - 1943-2020) tem tido a capacidade de se ressignificar no tempo e no espaço por 40 anos. Lotty finalmente descansa. Ela nos deixou faz poucas semanas, mas sua obra continua conosco, e a decisão da artista tem definido sua obra como herdável que continuará através de sua filha Alejandra, sua maior colaboradora.

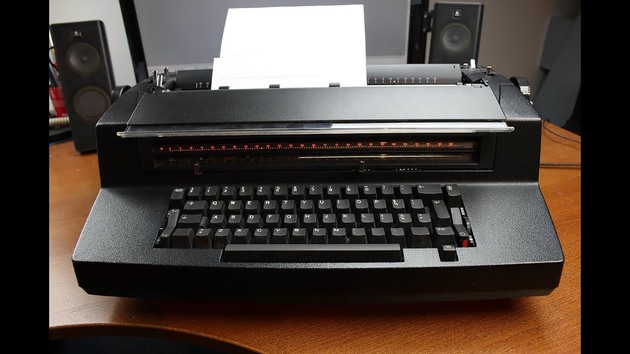

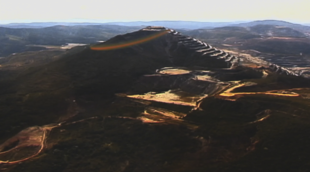

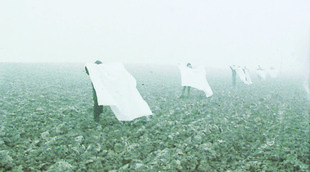

Em dezembro de 1979, enquanto amanhecia, Lotty Rosenfeld fez uma cruz no asfalto e mais outra e outra mais… Una milla de cruces sobre el pavimento (Uma milha de cruzes sobre o asfalto) é uma intervenção no espaço público e site specific que começa com a intervenção da linha descontínua da Calle Manquehue, rua que ganhou seu nome em Mapudungún, língua nativa da etnia Mapuche que significa “lugar dos condores”. O trecho da intervenção se localiza, paradoxalmente, entre duas avenidas: Avenida Los Militares y Avenida Kennedy, cujos nomes evocam o poder militar, por um lado, e, por outro, o poder dos Estados Unidos; este ponto está localizado no lado leste da cidade de Santiago de Chile. As linhas descontínuas da rua, como anuncia o título, receberam a intervenção por uma milha, ou 1,6 quilômetros, – processo que levou cerca de quatro horas – uma a uma foi alterada por uma fita branca vertical que aderiu ao asfalto por meio do uso de cola, formando o sinal +.

No ano seguinte, Lotty realizou uma instalação multicanal no mesmo lugar projetando um vídeo em duas telas de grande formato com o registro da ação realizada em dezembro do ano anterior. E em outra tela foi feita a projeção de um filme de 35mm no “bandejón” central da Calle Manquehue. As projeções tinham aproximadamente a duração de uma hora e apresentavam as imagens editadas da ação de 1979 em movimento. Ressalta-se que nem o vídeo ou o filme de 35mm tiveram as imagens tratadas, já que era o inicio do uso, por Rosenfeld, de filmagens como registro. Um signo público de sentido disciplinar único é transferido por meio de um ato direto e preciso de desobediência a um novo eixo de interpretação que vai do voto eleitoral ao símbolo da morte ou à adição. Essa não foi apenas sua primeira intervenção no espaço público, se não também o início de uma linguagem em si, que tem guiado – às vezes diretamente e outras indiretamente – boa parte de sua trajetória subsequente. A ação se repetiu por 40 anos em diferentes lugares do mundo, realizando uma única cruz, geralmente em lugares de poder político e econômico: na Casa Branca, em Washington; no Allied Checkpoint, em Berlim; na fronteira entre Chile e Argentina; no palácio de governo La Moneda, em Santiago de Chile e em vários outros locais. A ação foi repetida como um alinha de cruzes em Kassel, na Alemanha, em 2007, durante a Documenta 12; em Nova York, USA e em Cali, na Colômbia, em 2008, e ainda em Sevilha, na Espanha, no ano de 2013.

Por Alexia Tala

Lotty Rosenfeld

1943, Santiago, Chile.

2020, Santiago, Chile.

Os sinais pelos quais a circulação está organizada – bens, sujeitos, políticas, violência – têm sido os pilares do trabalho visual de Lotty Rosenfeld. Desde que realizou seu gesto de intervir nas linhas que dividem as vias de trânsito das avenidas de Santiago (1979), onde inscreveu seu emblemático sinal +, uma forma específica de questionar os mandatos foi criada literalmente e simbolicamente. Isso trouxe uma desconstrução da aparência natural de diversas ordenanças, pois a partir de uma aparente simplicidade, a primeira incursão visual instalou uma proliferação dos sentidos, e pensava-se ser um cidadão, rebelde e ação de arte de rua. Conceito que buscou a rua justamente quando o espaço público era ocupado pelo regime militar violento, invasivo e excludente. Assim, o trabalho de Rosenfeld implicava uma escolha estética e política. A construção desse signo + foi expandindo e iniciou uma nova etapa estética-teórica, na medida em que o sinal foi estabelecido como uma reclamação e confronto oposto a outros espaços hegemônicos de poder. Desta forma, o sinal se transformou em "arma crítica".

Desde 1985, Lotty Rosenfeld buscou estabelecer novas conexões, integrando-se às matrizes visuais de trabalho que continuaram apontando para a mecânica desconstrutiva, através do reprocessamento de imagens tiradas da televisão pública.

-

Héctor Zamora, Photokinetic, 2020

-

Re-Construtivo, 2020

Analivia Cordeiro

-

Forest Warrior – Xondaro Ka’aguy Reguá, 2020

ANGRY duo (Bruno Silvia e Gabe Maruyama)

-

Ouragualamalma, 2020

Eder Santos

-

Encruzidança, 2018

Kelly Santos e Naná Prudêncio

-

Vidbits, 1974

Alvy Ray Smith

-

Do Peito ao Prumo, 2020

Tothi dos Santos

-

The Trip, 1976

José Roberto Aguilar

-

Sunstone, 1979

Alvy Ray Smith

-

Tudo Está Dito, 1974

Augusto de Campos

-

Hommage a Mondrian, 1972

Jean Otth

-

Flesh I e Flesh II, 2004

Analivia Cordeiro

-

Limiar, 2015

Regina Silveira

-

Homenagem a George Segal , 1985

Lenora de Barros

-

Bronze Revirado, 2011

Pablo Lobato

-

Landscape for White Squares, 1972

Anthony McCall

-

VT Preparado AC/JC, 1985

Walter Silveira e Pedro Vieira

-

Places of Power, Waterfall, 2013

Marina Abramovic

-

Una Milla de Cruces Sobre el Pavimento, 1979

Lotty Rosenfeld

-

Alvos, 2017

Lenora de Barros

-

Ituporanga, 2010

Caio Reiseiwtz

-

Nas Coxas, 2018

Héctor Zamora

-

Non Plus Ultra, 1985

Tadeu Jungle

-

Há Casas, 2018

Rochelle Costi

-

0=45 Versão I, 1974

Analivia Cordeiro

-

Dormindo Acordada, 2011

Fabiana de Barros & Michel Favre

-

Earthwork, 1972

Anthony McCall

-

O Pulsar, 1975

Augusto de Campos

-

Actualidades / Breaking News, 2016

Liliana Porter

-

Campo, 1976

Regina Silveira

-

Tumitinhas, 1998

Eder Santos

-

Corda, 2014

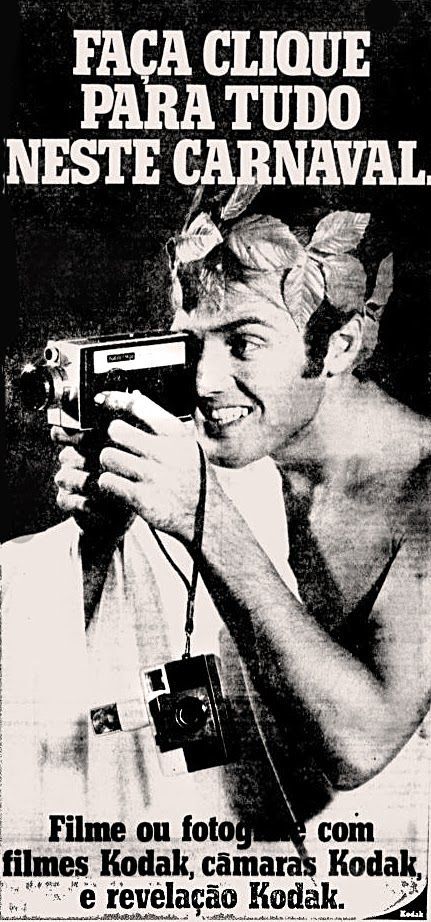

Pablo Lobato

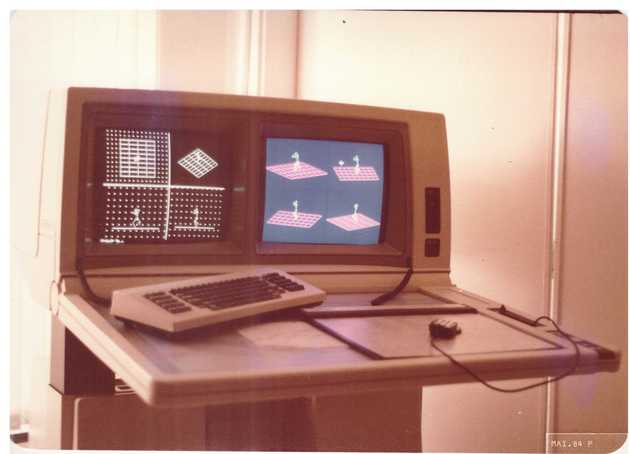

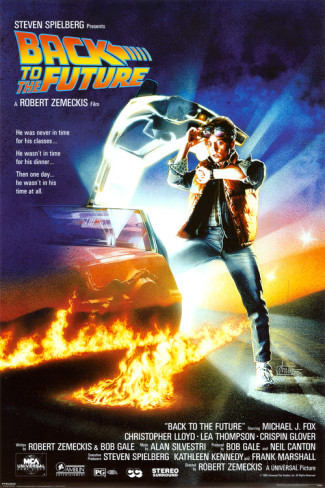

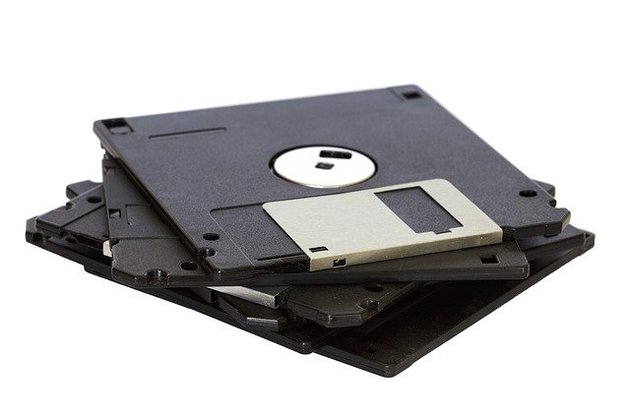

Aqui você verá vídeos históricos. Enquanto uns são praticamente inéditos, outros são consagrados pela história da arte. Em seus mais de 50 anos de existência, a vídeoarte é uma mídia que se caracteriza por sua enorme flexibilidade. Os formatos destes vídeos passaram por mais de dez variações: desde o início, com as grossas fitas U-Matic ou Betacam, por exemplo, até os pequenos e atuais pen-drives com suas enormes capacidades. Conhecer as transformações as quais essas obras sofreram é, hoje em dia, muito mais interessante do que se poderia pensar, considerando a acessibilidade atual da tecnologia, além da possibilidade de conhecer as fontes originais nos faz compreender que são justamente esses instrumentos que formatam o nosso mundo e a nossa percepção. Esta exposição tem o objetivo de mostrar como esses dispositivos existentes no passado podem nos ajudar a compreender e complementar o resultado artístico como um todo.

O modo de exibição também variou muito: hoje existem inúmeras plataformas, desde celulares de pequena dimensão, até projetores 4K – Ultra HD, com grande extensão e qualidade excepcional. Mais uma vez, seguindo os rumos e as necessidades da nossa história, essa arte se reinventa e adquire um valor único quando entendemos, sentimos, compartilhamos e discutimos sua capacidade em traduzir um momento histórico, um lugar geográfico específico, ou mesmo um comportamento particular que se torna universal.

Neste momento de isolamento social, a câmera de vídeo ganhou status de principal meio de comunicação visual, o único canal entre aqueles a quem queremos comunicar. Com isso em mente, podemos avaliar o significado de se expressar através de uma câmera. Podemos ainda compreender melhor a razão da qual os artistas escolheram este recurso para contar suas histórias e se posicionar no mundo, ressignificando-o através das lentes e do olhar do espectador.

Mesmo hoje sendo tão próxima de nós, a câmera de vídeo nos impõe condições e a principal delas é que tudo o que queremos expressar deve se encaixar dentro de um retângulo, presente em todos os dispositivos de exibição de vídeo, desde aparelhos celulares até datashows. Ao mesmo tempo, há o desafio de fazer com que o espectador perceba a mensagem e seja instigado a imaginar o que acontece fora deste retângulo. É um jogo, e ao mesmo tempo, uma ditadura: a ditadura do retângulo. Nessa obrigação de enquadrar o mundo dentro de um espaço restrito condicionamos nosso cérebro a pensar assim e nossa percepção se altera de acordo com esses padrões. Vemos a realidade como algo a ser adaptado pelo nosso principal instrumento atual de expressão: o vídeo.

O vídeo é visual e sonoro, mas é a realidade que nos oferece as sensações físicas. O grande desafio para o artista, dessa forma, é transmitir a riqueza e a complexidade da realidade com os recursos limitados dessa tecnologia. É intrigante observar como a genialidade e talento de cada artista provoca em nós sensações que vão além das restritivas soluções técnicas e até das experiências humanas. Através desse retângulo e dos recursos audiovisuais, cada artista cria sua poética e compõe uma obra única. Além disso, independente da percepção individual do espectador, há de se considerar o significado histórico e artístico contido em cada vídeo. É importante ainda apreciar os aspectos diversos do contexto de cada período, seus valores e possibilidades. Por isso, cada uma dessas obras pode ser vista mais de uma vez, e a cada oportunidade surge um novo olhar, assim como acontece com as telas penduradas nas paredes. Assim como a pintura, o vídeo também é uma tela, mas com movimento e som: este é o princípio base da vídeoarte.

Nenhuma outra mídia conseguiu trilhar tão bem o caminho para a contemporaneidade como a vídeoarte. Ao longo de sua trajetória foi eliminando os obstáculos, aperfeiçoando-se, até conquistar seu lugar definitivo nas artes visuais. Não só foi assimilada como recurso pelas mais diversas linguagens, como carrega em si a capacidade de agregar os elementos da arte, como por exemplo a tradição clássica da tela emoldurada ou a narrativa literária. Nesse sentido metalinguístico, como ela pode ser renovadora? Pense nisso enquanto assiste aos vídeos.

Os vídeos aqui escolhidos para serem apresentados online são legítimos, de alta qualidade artística, concebidos primeiramente para serem mostrados em formato original. Trata-se de uma curadoria genuína e autêntica, realizada para transmitir as ideias e as formas de pensamentos que nos fazem pensar, além de nos envolver com as poéticas intrigantes das épocas em que foram concebidos.

Ao assistir aos vídeos, permita-se transportar para o período em questão: anos de 1970, 80, 90 ou os anos 2000, e ao mesmo tempo experiencie com eles o que há de universal e duradouro.

Analivia Cordeiro,

março 2020

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Analivia Cordeiro, PhD, bailarina, coreógrafa, videoartista, arquiteta, pesquisadora corporal, curadora da coleção Waldemar Cordeiro. Considerada a primeira videoartista do Brasil (1973) e uma das pioneiras da computer dance mundial, criou vídeos, espetáculos multimídia, o software Nota-Anna de notação de movimento humano e um sistema de alfabetização de português em vídeo. www.analivia.com.br

Em breve você verá aqui a programação completa da exposição.