LB/Festival de Vídeo Online

A cada semana, a partir do dia 28 de abril, a Luciana Brito Galeria disponibilizou um novo vídeo, uma nova experiência, que ficará em nosso site por tempo indeterminado. Assim, você pode ver e rever, quantas vezes e quando quiser. O objetivo foi propor uma reflexão sobre um conjunto significativo de trabalhos tanto de artistas que são representados por nós, quanto de outros que achamos relevantes para a proposta. O vídeo da semana é "Photokinetic" (2020), de Héctor Zamora (México). Acompanhe!

Curadoria: Analivia Cordeiro

Texto Curatorial: leia aqui

Sunstone, 1979

Circulating Video Library Catalog (1983), curated by Barbara J. London, Assistant Curator, Video, Department

of Film, The Museum of Modern Art, New York City, NY: MOMA, 27: “Sunstone (1979) U.S.A. By Ed Emshwiller.

Computer animation by Alvy Ray Smith, Lance Williams, and Garland Stern at the New York Institute of Technology.”

"Olá, Cork,

Eu bolei isso aqui na minha cabeça no voo volta de Atlanta, ontem.

Salvem, todos!

Vocês estão prestes a assistir uma das primeiras animações feitas em computador, Sunstone, e também estão prestes a ouvir a interpretação musical que Cork e seu grupo fizeram do filme. Também é uma estreia. Opa, espere aí! – vocês devem estar dizendo: o Cork já fez isso antes, logo ali no The Acorn Theater, em Michigan, um ano atrás. Bem: sim e não. Ele tocou com uma cópia deteriorada da obra, uma versão de YouTube. O que você vai ver agora é Sunstone em uma versão integralmente reconstruída, a partir da fita original, muito próxima de sua glória original. E aí tem uma história que conecta Cork, eu e vocês.

Aliás, eu me chamo Alvy Ray Smith. Eu fiz Sunstone uns 30 e tantos anos atrás com meu grande amigo e mentor, Ed Emschwiller – o “Emsh”, como a gente o chamava. Era assim que ele assinava as suas artes para as capas das revistas populares de ficção científica dos anos 1950 – como Galaxy Science Fiction. Emsh era certamente um desbravador nato, e mestre de muitas formas de arte: pintura a óleo abstrata, filmes em 16 milímetros, vídeo e, por fim, animação por computador. Ele é associado a todos esses campos – em museus em todo o mundo por uma arte ou outra – e foi o primeiro, um pioneiro mesmo, em quase todas elas. Sunstone foi uma das primeiras peças de animação por computador, e está na coleção do MoMA (Museu de Arte Moderna) em Nova York. Emsh terminou sua carreira como um querido Reitor da Cal Arts (o Instituto de Artes da Califórnia) no sul da Califórnia, um conselheiro para uma geração de artistas. A cerimônia em sua memória, que aconteceu lá, foi a mais incrível que eu já vi – horas e horas de sincero amor expresso por tantos de nós que tivemos nossas vidas transformadas por essa pessoa maravilhosa. Se o Emsh tivesse podido ver aquilo, ele certamente teria rido da maneira que era a sua marca registrada, como um contagiante e profundo Papai Noel: “Ho ho ho”.

Eu tenho muito orgulho de Sunstone. Eu fui de Long Island, onde Emsh e eu fizemos o filme, para o norte da Califórnia, onde eu cofundei a Pixar, a empresa de animação por computador. Embora eu até goste dos filmes da Pixar – orgulho de pai, sabe... – eu tenho mais orgulho de Sunstone do que de qualquer dos filmes da Pixar. Quando pela primeira vez eu ouvi falar do Corky Siegel, tudo o que eu tinha de Sunstone era também uma degradada cópia de YouTube, pelo menos era o que eu imaginava.

Fui avisado pelo Google no ano passado que “meu” Sunstone tinha sido apresentado no Acorn acompanhado de alguns bluesmen de Chicago, ou foi isso que entendi. Falei com um repórter que me colocou em contato com o Cork. Além de ficar assustado com o fato de que alguém mais gostava de Sunstone, a ponto de tocar com o filme (e assim homenageá-lo, em minha opinião), eu pensei que talvez ele tivesse uma cópia do filme melhor do que a minha. Mas não! Ele também só tinha a versão de YouTube. Afe! Ele estava mostrando aquela versão decrépita na tela grande. Resolvi então procurar o MoMA para ver se eles tinham uma versão melhor, para que tanto o Cork como eu pudéssemos usar. Mas esse esforço foi em vão, não sei por quê. Minha amiga que é curadora no MoMA nunca respondeu minha mensagem. Talvez ela não esteja mais lá.

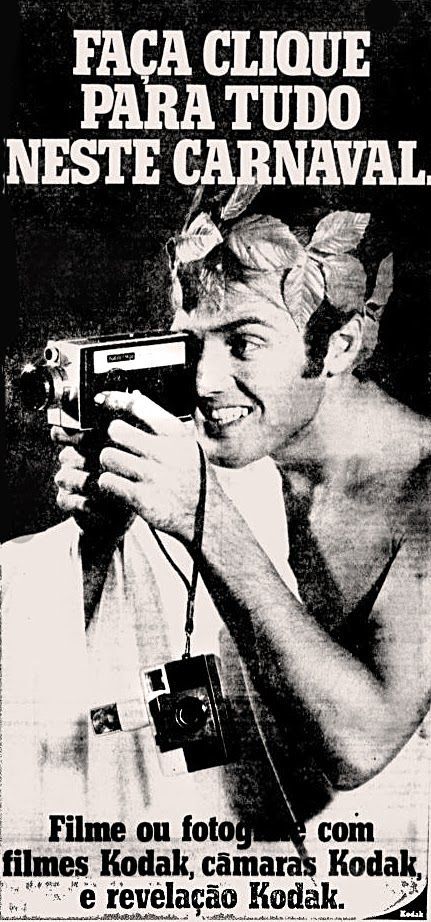

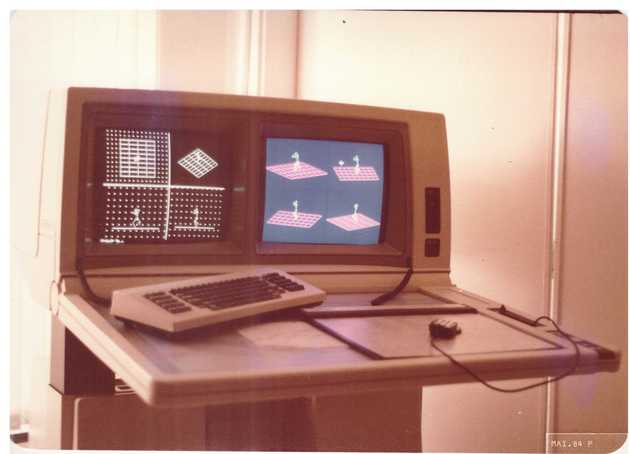

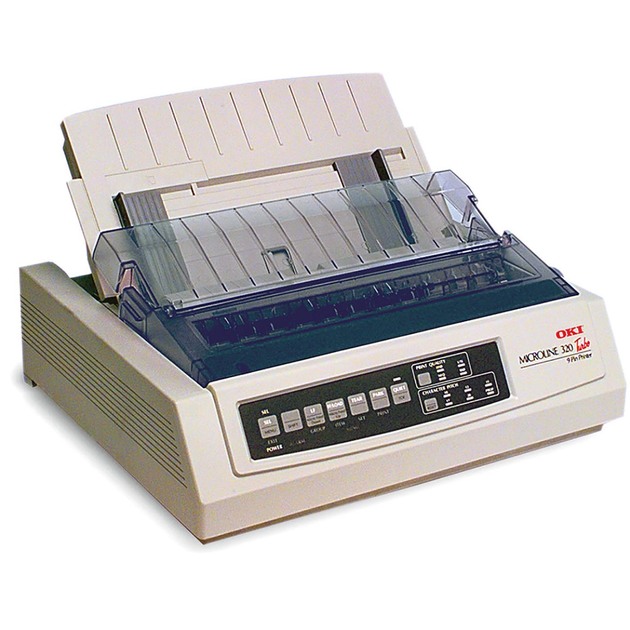

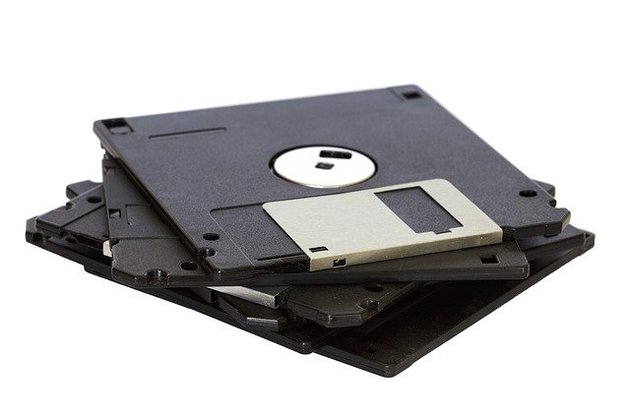

Bom, como provavelmente muitos vocês também fazem, eu tenho carregado a minha vida em caixas por aí, mudando de casa em casa, de estado em estado, por décadas. Eu não lembro o que tem dentro da maioria dessas caixas. Mas um dia eu estava vasculhando as caixas por alguma razão qualquer, nada a ver com essa história, e me deparei com a fita máster de Sunstone! Estava num antigo formato de fita de vídeo, chamado “quad de 2 polegadas”, porque o filme tinha sido feito no final dos anos 1970 em um gravador de rolo tipo Ampex Quad de 2 polegadas, do mesmo tipo usado nas redes de televisão naquela antiga era para gravações de alta qualidade.

Fiquei animadíssimo com essa descoberta, mas também meio consternado. Uma fita de vídeo tão antiga poderia simplesmente não rodar mais. Fita de vídeo envelhece. A superfície com carga magnética da fita vira poeira e a fita envelhece. Não apenas isso, mas não existem mais tocadores de fita Amplex Quad de 2 polegadas. Era o que eu pensava até que eu joguei no Google “ampex quad” e encontrei um colega em Oregon que tinha restaurado um desses velhos monstros! Quem diria? Falei com ele sobre Sunstone, Emsh, Corky, mim, etc., e ele se voluntariou a rodar a minha velha fita e convertê-la para um formato digital atual, um DVD – porque era uma obra historicamente importante. Este cara merece um grande crédito. Trata-se de Park Seward, o cara que fez um ótimo trabalho de restauração, como vocês verão. Parece muito com Sunstone original. E é absolutamente diferente da versão de YouTube. Obrigado, Park!

Antes de deixar Corky e a Chamber Blues mandarem bala, queria apenas dizer algo sobre como Sunstone foi feito. Trata-se, também, de uma improvisação de jazz.

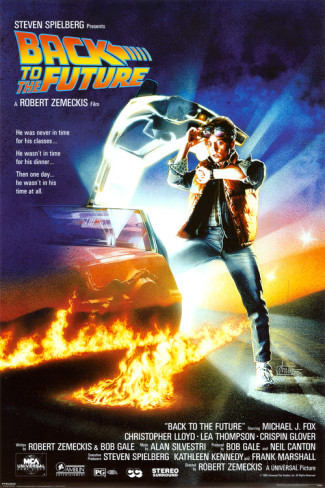

O grupo de pessoas que hoje é conhecido como Pixar começou em Long Island nos anos 1970. Um dia, Emsh apareceu no nosso lab, dizendo que tinha uma bolsa Guggenheim e um prazo de seis meses, e ele queria fazer um filme de 3 horas usando nossa tecnologia computadorizada. Caímos na gargalhada! Emsh, bastante surpreso, insultado em sua dignidade, perguntou o que ele tinha dito de tão engraçado. Tivemos que explicar que estávamos nos primeiros tempos da animação por computação. Com muita sorte, ele conseguiria uns 3 minutos de filme. De fato, Sunstone é só um pouco mais longo que 3 minutos. Para colocar nossa risada em perspectiva, é preciso saber que os computadores 30 anos atrás eram 1 milhão de vezes mais lentos do que hoje! Ou tinham 1 milhão de vezes menos memória. Ou custavam 1 milhão de vezes mais. Por qualquer ângulo que se olhe, o mundo dos computadores de 1979 era 1 milhão de vezes pior do que é hoje. Por isso levamos 20 anos desde a nossa primeira ideia de realizar um filme digital em 1975, em Long Island, até a sua concretização, o filme Toy Story, em 1995, já como Pixar, na Califórnia.

Mas depois que a risada passou e Emsh entendeu as restrições, ali começou a mais profunda parceria artística de minha carreira. Emsh se tornou uma espécie de pai para mim (nós dois tínhamos cabelo comprido, o dele branco, o meu preto, saídos direto do final dos anos 1960 na Califórnia). Emsh era apaixonado o suficiente por tecnologia para ceder quando tinha que ceder para se compatibilizar com os dolorosos limites da computação daquele tempo. Eu era artista o suficiente (pintei a óleo e acrílica por muitos anos antes de descobrir a pintura por computador) para ceder aos caprichos artístico do Emsh. Uma típica sessão com ele poderia acontecer assim: ele dizia, por exemplo, “eu quero empurrar um homem através de um muro de concreto”. Eu ria e dizia: “Emsh, vamos conseguir fazer isso no futuro, mas ainda não. Eu levaria meses pra escrever o código e meses pra esperar a máquina executar isso. Mas se você mudar o conceito para isso aqui, podemos conseguir fazer [e eu apresentava uma sugestão artística que eu sabia que poderia fazer acontecer em um tempo razoável]”. Ele então dizia: “Bom, nesse caso, você pode mudar essa ideia para isso? [e propunha uma modificação artística daquilo que eu tinha oferecido]”. E ficávamos naquele vaivém até finalmente convergirmos para uma solução, que fosse factível tanto artística como tecnologicamente. Eu implementava e então fazíamos a mesma coisa para a próxima cena. É por isso que eu falo que fazíamos uma improvisação visual – pelo menos o processo foi assim. Vocês só precisam imaginar que o relógio rodava MUUUITO DEVAGAR. Ele mandava um riff, então eu respondia com outro riff, aí ele trabalhava com aquilo, etc. etc. O que estou tentando dizer é que o processo era muito divertido, surpreendente e agregador – e extraiu o melhor de nós e gerou um resultado do qual nós dois nos orgulhamos.

Chega desse meu papo sem fim. Obrigado por me ouvirem. Que tal agora vermos o que o Cork vai fazer com a nova e aperfeiçoada versão de Sunstone? Vamos?"

Alvy Ray Smith

Alvy Ray Smith

Dr. Alvy Ray Smith: Cofundou duas startups de sucesso: Pixar – ver os documentos de fundação da Pixar (vendida para a Disney) e Altamira (vendida para a Microsoft). Primeiro diretor de computação gráfica na Lucasfilm. Membro original do Computer Graphics Lab no Instituto de Tecnologia de Nova York. Primeiro pesquisador em Computação Gráfica na Microsoft. Estava na Xerox PARC quando do nascimento do computador pessoal (PC), da internet e dos primeiros pixels coloridos. Recebeu dois Prêmios Acadêmicos técnicos, pelo canal alfa e os sistemas de pintura digital. Inventou os primeiros programas de pintura em cores, o sistema de cores HSV (ou HSB), e o canal alfa. Dirigiu a “Genesis Demo” para Star Trek II: A Ira de Khan. Contratou John Lasseter e o dirigiu em The Adventures of André & Wally B. Propôs e negociou o sistema de produção de animação por computador da Disney, o CAPS, vencedor do Oscar. Participou decisivamente, como membro do Conselho Diretor, do lançamento do Projeto Ser Humano Visível da Biblioteca Nacional de Medicina. Testemunha especial em um processo que conseguiu invalidar cinco patentes que ameaçavam o Adobe Photoshop. Atuou no desenvolvimento do padrão HDTV, em defesa da varredura progressiva. É Ph.D. pela Universidade de Stanford e doutor honorário pela Universidade do Estado de Novo México. Membro da Academia Nacional de Engenharia. Membro da Associação Americana para o Avanço da Ciência e membro da Associação Americana de Genealogistas. Publicou amplamente nas áreas de teoria da ciência da computação, computação gráfica e genealogia acadêmica. Criador de muitas obras de arte computacional, inclusive Sunstone, do acervo do MoMA – Museu de Arte Moderna de Nova York. Detém quatro patentes. Atualmente, está escrevendo o livro: A Biography of the Pixel [Uma biografia do pixel]. Conselheiro na Baobab Studios, premiada startup de realidade virtual [VR] no Vale do Silício. Para mais detalhes, ver: <alvyray.com>.

-

Héctor Zamora, Photokinetic, 2020

-

Re-Construtivo, 2020

Analivia Cordeiro

-

Forest Warrior – Xondaro Ka’aguy Reguá, 2020

ANGRY duo (Bruno Silvia e Gabe Maruyama)

-

Ouragualamalma, 2020

Eder Santos

-

Encruzidança, 2018

Kelly Santos e Naná Prudêncio

-

Vidbits, 1974

Alvy Ray Smith

-

Do Peito ao Prumo, 2020

Tothi dos Santos

-

The Trip, 1976

José Roberto Aguilar

-

Sunstone, 1979

Alvy Ray Smith

-

Tudo Está Dito, 1974

Augusto de Campos

-

Hommage a Mondrian, 1972

Jean Otth

-

Flesh I e Flesh II, 2004

Analivia Cordeiro

-

Limiar, 2015

Regina Silveira

-

Homenagem a George Segal , 1985

Lenora de Barros

-

Bronze Revirado, 2011

Pablo Lobato

-

Landscape for White Squares, 1972

Anthony McCall

-

VT Preparado AC/JC, 1985

Walter Silveira e Pedro Vieira

-

Places of Power, Waterfall, 2013

Marina Abramovic

-

Una Milla de Cruces Sobre el Pavimento, 1979

Lotty Rosenfeld

-

Alvos, 2017

Lenora de Barros

-

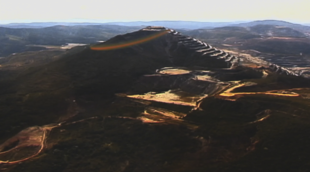

Ituporanga, 2010

Caio Reiseiwtz

-

Nas Coxas, 2018

Héctor Zamora

-

Non Plus Ultra, 1985

Tadeu Jungle

-

Há Casas, 2018

Rochelle Costi

-

0=45 Versão I, 1974

Analivia Cordeiro

-

Dormindo Acordada, 2011

Fabiana de Barros & Michel Favre

-

Earthwork, 1972

Anthony McCall

-

O Pulsar, 1975

Augusto de Campos

-

Actualidades / Breaking News, 2016

Liliana Porter

-

Campo, 1976

Regina Silveira

-

Tumitinhas, 1998

Eder Santos

-

Corda, 2014

Pablo Lobato

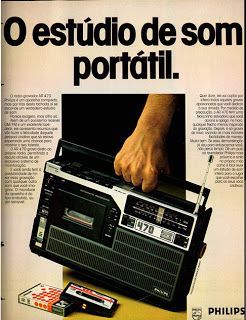

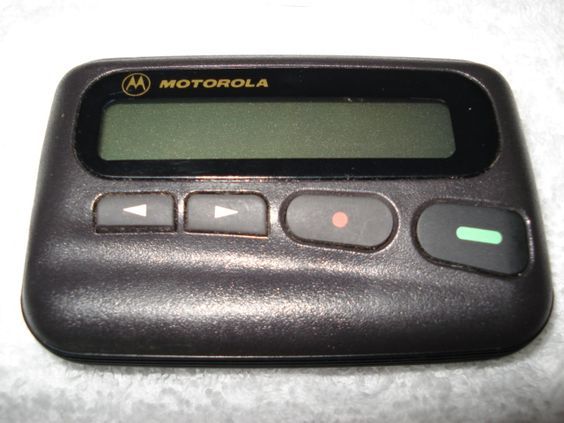

Aqui você verá vídeos históricos. Enquanto uns são praticamente inéditos, outros são consagrados pela história da arte. Em seus mais de 50 anos de existência, a vídeoarte é uma mídia que se caracteriza por sua enorme flexibilidade. Os formatos destes vídeos passaram por mais de dez variações: desde o início, com as grossas fitas U-Matic ou Betacam, por exemplo, até os pequenos e atuais pen-drives com suas enormes capacidades. Conhecer as transformações as quais essas obras sofreram é, hoje em dia, muito mais interessante do que se poderia pensar, considerando a acessibilidade atual da tecnologia, além da possibilidade de conhecer as fontes originais nos faz compreender que são justamente esses instrumentos que formatam o nosso mundo e a nossa percepção. Esta exposição tem o objetivo de mostrar como esses dispositivos existentes no passado podem nos ajudar a compreender e complementar o resultado artístico como um todo.

O modo de exibição também variou muito: hoje existem inúmeras plataformas, desde celulares de pequena dimensão, até projetores 4K – Ultra HD, com grande extensão e qualidade excepcional. Mais uma vez, seguindo os rumos e as necessidades da nossa história, essa arte se reinventa e adquire um valor único quando entendemos, sentimos, compartilhamos e discutimos sua capacidade em traduzir um momento histórico, um lugar geográfico específico, ou mesmo um comportamento particular que se torna universal.

Neste momento de isolamento social, a câmera de vídeo ganhou status de principal meio de comunicação visual, o único canal entre aqueles a quem queremos comunicar. Com isso em mente, podemos avaliar o significado de se expressar através de uma câmera. Podemos ainda compreender melhor a razão da qual os artistas escolheram este recurso para contar suas histórias e se posicionar no mundo, ressignificando-o através das lentes e do olhar do espectador.

Mesmo hoje sendo tão próxima de nós, a câmera de vídeo nos impõe condições e a principal delas é que tudo o que queremos expressar deve se encaixar dentro de um retângulo, presente em todos os dispositivos de exibição de vídeo, desde aparelhos celulares até datashows. Ao mesmo tempo, há o desafio de fazer com que o espectador perceba a mensagem e seja instigado a imaginar o que acontece fora deste retângulo. É um jogo, e ao mesmo tempo, uma ditadura: a ditadura do retângulo. Nessa obrigação de enquadrar o mundo dentro de um espaço restrito condicionamos nosso cérebro a pensar assim e nossa percepção se altera de acordo com esses padrões. Vemos a realidade como algo a ser adaptado pelo nosso principal instrumento atual de expressão: o vídeo.

O vídeo é visual e sonoro, mas é a realidade que nos oferece as sensações físicas. O grande desafio para o artista, dessa forma, é transmitir a riqueza e a complexidade da realidade com os recursos limitados dessa tecnologia. É intrigante observar como a genialidade e talento de cada artista provoca em nós sensações que vão além das restritivas soluções técnicas e até das experiências humanas. Através desse retângulo e dos recursos audiovisuais, cada artista cria sua poética e compõe uma obra única. Além disso, independente da percepção individual do espectador, há de se considerar o significado histórico e artístico contido em cada vídeo. É importante ainda apreciar os aspectos diversos do contexto de cada período, seus valores e possibilidades. Por isso, cada uma dessas obras pode ser vista mais de uma vez, e a cada oportunidade surge um novo olhar, assim como acontece com as telas penduradas nas paredes. Assim como a pintura, o vídeo também é uma tela, mas com movimento e som: este é o princípio base da vídeoarte.

Nenhuma outra mídia conseguiu trilhar tão bem o caminho para a contemporaneidade como a vídeoarte. Ao longo de sua trajetória foi eliminando os obstáculos, aperfeiçoando-se, até conquistar seu lugar definitivo nas artes visuais. Não só foi assimilada como recurso pelas mais diversas linguagens, como carrega em si a capacidade de agregar os elementos da arte, como por exemplo a tradição clássica da tela emoldurada ou a narrativa literária. Nesse sentido metalinguístico, como ela pode ser renovadora? Pense nisso enquanto assiste aos vídeos.

Os vídeos aqui escolhidos para serem apresentados online são legítimos, de alta qualidade artística, concebidos primeiramente para serem mostrados em formato original. Trata-se de uma curadoria genuína e autêntica, realizada para transmitir as ideias e as formas de pensamentos que nos fazem pensar, além de nos envolver com as poéticas intrigantes das épocas em que foram concebidos.

Ao assistir aos vídeos, permita-se transportar para o período em questão: anos de 1970, 80, 90 ou os anos 2000, e ao mesmo tempo experiencie com eles o que há de universal e duradouro.

Analivia Cordeiro,

março 2020

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Analivia Cordeiro, PhD, bailarina, coreógrafa, videoartista, arquiteta, pesquisadora corporal, curadora da coleção Waldemar Cordeiro. Considerada a primeira videoartista do Brasil (1973) e uma das pioneiras da computer dance mundial, criou vídeos, espetáculos multimídia, o software Nota-Anna de notação de movimento humano e um sistema de alfabetização de português em vídeo. www.analivia.com.br

Em breve você verá aqui a programação completa da exposição.